Monitoring

Up to 16 contemporary media installations and sculptures by up-and-coming as well as well-known artists will be presented at the exhibition Monitoring. Mehr über das Konzept

Google Translate movies – Sveta Antonova (Kulturbahnhof)

22 computer monitors are mounted flat against the wall, each one connected to its own playback device, cables hanging down. The monitors show “harbor poems” and “urban text” – two compilations of 110 videos of 30 seconds each, which Sveta Antonova shot at the harbor and in the urban space of Falmouth (Cornwall, England) put together for her work GOOGLE TRANSLATE MOVIES.

The work almost seems like strung-together photographs, if it wasn’t for the text fragments, which appear and disappear between the images or transform into a new word. It seems as though the words were lacking the final decisiveness to remain in the images. The title of the work provides the information of their origin: They were generated by “Google Translate”, a program for automatic translations operated by Google. By means of visual sign and word recognition, the program claims to be able to recognize words on traffic signs or even restaurant menus. But if there happen to be enough lines and forms on the pictures besides the text fragments, the program sees these as a complete page of text. This circumstance is taken advantage of by the artist and determines her selection of images. Additionally, she has Google Translate “translate” the text from English to English. This unusual approach puts focus on the function and work mode of this program and also lets us question it. Even though in this case the translation is unnecessary, the program applies its translation methods. In the shortest time it refers to huge masses of information, mainly based on UN materials published in six different official languages since 1957. In addition, the program uses all bilingual materials that have been uploaded to the web. It then searches for the respective words and puts them into already existing contexts.

All of a sudden we read words like “BAY”, “SHARK”,” I LIFE” or “ELF” above the image of a sail boat – all at places, that originally showed parts of the sky and parts of the sail boat but did not contain any text fragments. Cases like these raise the question whether the program solely reacts to geometric forms or also takes in the maritime ambience. Other images show how existing words are replaced by new ones – an unintentional humorous performance of the program. The harbor master of the Cornwall Council for instance points to a sign reminding good behaviour: “ANY SINGLES LEFT ON TOP OF THIS QUAY WANTS BE REMOTED AT OWNERS EXCESSES”. Another sign reminds us: “HAVE YOU PAID AND DISPLACED YOUR TICKET”? A strange parody emerges.

Kassel, Falmouth 2015 / 22 Monitore, 22 Thin Clients

Фильм для воображаемой музыки (Film for Imaginary Music) – Mikhail Basov, Natalia Basova (Kulturbahnhof)

The vinyl disc is a nostalgic image, one of those phantoms of the past that constantly looks for a way to return to our consciousness, which is directed primarily to the present, to the new. In FILM FOR IMAGINARY MUSIC[1] an old vinyl disc rolls uninterruptedly along a seashore without any visible external force, overcoming obstacles like a living being. A fragile object, which we are so afraid to drop on the floor, here by the sea, on sand, amidst rocks, shows incredible qualities as if it has just been waiting for a convenient moment. Who would have thought that, as soon as it finds itself on a seashore, in a dangerous and alien environment, such a metamorphosis could happen?

The mere thought of it is fanciful and could come to our mind maybe only as a metaphoric line about the clash between the world of music (and possibly that of culture and art in general) and the world of nature’s elements. Except that the former does not fight but reach for the latter, while magically transforming itself. However, this image was materialized not in a literary text but in real life, resulting in the event taped on this video (practically no computer effects were used in the film). Here is an event that looks like magic, a daydream or animation;precisely that: Life that imitates animation, not the other way around.

Here is an object that goes beyond its own boundaries without losing its material form. The disc is no longer just media, a carrier of information, a mediator – it becomes free and self-sufficient. We will never hear the music recorded on it. The sea wind is its only player and only listener. But when we watch it roll on sand and jump over rocks, we can imagine any sounds its vinyl surface might bear. Which means that this video’s soundtrack may end up counting more compositions than any other film is capable of accommodating.

It is the happy moment that makes the video by Natalija Basova and Mikhail Basov a particular happening;a fascination, which is as simple as it is enchanting. We regard it and cannot help but feel amazed. With this work the artist duo lines up with a long tradition of such orchestration, in which things suddenly come to life that before seemed carelessly left behind, similar to the films by Igor and Svetlana Kopystiansky in the mid 1990s. Here the wind is the motor for animistic magic. Since ancient times, wind has been used as a way of bringing things to life. Wind chimes rely on wind to produce sounds and artful movements. Irony has it that in this case a sound carrier remains silent and only therefore can become an image of rhythm and melody. The projection of the video as an installation enables us to follow this sound as though we were flying over the beach ourselves. Delighted by the gliding movement of the camera we follow the balancing act tumbling forward in a lightness freed from bodily heaviness.

[1] The title FILM FOR IMAGINARY MUSIC is a wordplay of a well-known among music fans genre “Music for imaginary films”

Taganrog 2014 / Video-Projektor, HD-Player (6:29 Min.)

Loophole for All – Paolo Cirio (Kulturbahnhof)

The center of LOOPHOLE FOR ALL consists of a list of over two thousand names of offshore companies with headquarters on the Cayman Islands. Paolo Cirio claims to have obtained the list through computer hacking, the results of which he then published on the website www.loophole4all.com. This publication provoked a statement on the “Cayman 27 News” assuring the servers of the company registries were safe, that there had not been a hacking incident and that Cirio’s claim was merely a fake. The concept of LOOPHOLE FOR ALL lies at the intriguing threshold between cyber activism, media hacking, data journalism and art.

Cirio, who already cooperated with Ubermorgen.com on projects like “Amazon Noir” or “Google Will Eat Itself”, creates his position as an artist very deliberately with irony and with an open attitude, which gives his projects a deeper more complex dimension. One of his trademarks lies in the strategy of finding special forms to transform immaterial things like findings from the internet, which initially only exist as data, into real objects and exhibits. Cirio calls this process materialization of information. In his most recent project “Overexposed - HD Stencils” for example he places monochrome portraits of US secret service employees into public spaces as graffiti via laser-cut stencils. Cirio also deals with abstract information in LOOPHOLE FOR ALL. The company names of the offshore companies were completely made up by their anonymous founders and are nothing but mere variables, a little detail in the complex system of tax fraud. Paolo Cirio finds an especially pointed form for this data. As a fictitious “assistant registrar” – but using his real name – he produces a “Certificate of Incorporation” for every one of these make believe companies, prints it as a document and sells it in the internet. In this way the existence of tax havens become a touchable experience. How absurd is it to hold a real document in your hands that is supposed to represent the existence of a fake company with anonymous owners?

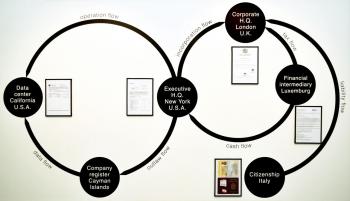

To prevent potential legal consequences from this project, Paolo Cirio developed his own firm structure with a Corporate H.Q. in London, Financial Intermediary in Luxemburg and Executive H.Q. in New York. Asked if he expected a reaction to his provocation, Cirio offers a different interpretation of the certificates he sells. From an art market perspective, the documents are nothing but picture data, which he – like many other artists – prints as an edition, signs and sells. In the project LOOPHOLE FOR ALL Paolo Cirio manages to reflect the staging of a computer hack, which plays with perceptions and realities and questions the meaning of art and authorship with much irony.

Im Rahmen der interdisziplinären Workshop-Tagung für Kunst, Medien und Netzkultur interfiction sprechen Paolo Cirio und Ivar Veermäe über ihre Arbeiten.

// In the course of the interdisciplinary conference and workshop summit interfiction Paolo Cirio and Ivar Veermäe will talk about their works.

New York 2013 / 2 Monitore, 2 HD-Player, 4 Kopfhörer, 5 gerahmte Drucke, 2 Wandbilder, Zertifikate (12 Min.)

Beklediğim Yer (Place That I Wait) – Özgür Demirci (Kulturbahnhof)

Nothing happens. The wind gently glides through the awnings and makes the parasols and flags flutter. In marginal locations, ignored by historiography with obscured actual circumstances, terraces offer space for routine coffee drinking. On these little quasi-stages many chairs pair up with few people but every once in a while a chair is moved, a head turns, a shoulder is looked over, a coffee cup is held up and put down again. But nothing actually happens. It is almost as if one pressed down “play” and “pause” of an old video cassette player simultaneously, only to reside in the eternity of the most insignificant moment: one second forward, one second back. It is all but liberating in a meditative way to surrender fully to that moment. A tranquillity with an indescribable sense for the short moment trapped between future and past becomes transferable. Like the lightly hovering empty plastic bag in “American Beauty” (Sam Mendes, 1999) that – in spite of the banality of its appearance – seems to breathe out the essence of failed American dreams into the depressing suburb world. The moment withdraws from reality and distracts our thoughts to an alternative possible world that does not exist.

In his work PLACE THAT I WAIT Özgür Demirci shows ten cafés in the North and South of the politically separated island of Cyprus on two opposite projections facing each other. On the one side one can observe Greek cafés and on the other side Turkish ones. As the observer of the installation, one finds oneself and one’s necessary viewpoint within this fragile zone: in between but not in the middle of it. Regarding both sides at once becomes a difficult task since one turns one’s back to the one while observing the other. This is a physical fact. But this situation between the cafés, between the cultural and political boundaries, between languages and traditions is also a space of close examination and relating. In this space it is possible to gain distance and find solutions that seem impossible in the scenery itself.

While the wind moves the flags, it also lets us sink into contemplation about what is and what could be. Between necessary truth and collective resignation in contemporary Europe the observation lets us pause in a continuum of reality: In the fluttering awning we see the memory of the present and astonishment by the world, like a daydream, both leading to creative inactivity. Cézanne once said that one had to give in to the motif and accept the impossibility to successfully pull it towards you. With this patient honouring of the undecided moment between future and past, Demirci searches for a symbolic “in between” in the banality of every day life of this (and other) politically explosive region. This “in between” marks a wave’s trough – a point in time that leaves the decision open.

Zypern, Türkische Republik Nordzypern 2013 / 2 Video-Projektoren, 2 HD-Player (29 Min.)

Technoviking Archiv – Matthias Fritsch (Kulturbahnhof)

In 2000 Matthias Fritsch, more or less by chance, captured a scene with his camera at the so- called “Fuck Parade” in Berlin. On the one hand, the video seems like a snapshot, on the other hand it seems too perfect to be true. It focuses on a dancing, half-naked man, who seems like a giant from a different time.

When Fritsch published his art video “Kneecam No. 1” in the internet, it could not be foreseen how famous this digital recording would become: Up until today it has generated over 80 million documented clicks in the internet. The video’s popularity did not occur over night. Only after seven years and after an internet user linked the video to a porno site with the tag “Thor”, was the video noticed on a larger scale. A step to another video site followed and the protagonist as well as the video were named “Technoviking”. The era of an internet meme began – for not only the original video was shared. The internet community appropriated the video in a variety of ways. “Technoviking’s” dance style and gestures were reproduced in a manifold of fashions. Many of them used their own body, others relied on the original and some even created animations – in the end everything was newly uploaded to the internet. The fictional character “Technoviking” became a celebrated star.

But what if the respective person, who inspired the meme, remains in this role involuntarily? In 2009 the protagonist and his attorney contacted Fritsch and demanded to stop further publication of “Kneecam No. 1” and any connected commercial activity thereof. Fritsch immediately stopped all revenue from commercials and blocked his uploads – he continued using it solely offline within his archive, which he had set up for the “Technoviking”. At this point though, the distribution of the internet video is no longer in the maker’s hands. Three years later the dancer sued Fritsch and in 2014 the verdict became binding: The giant is to be censured out of the publicity – online as well as offline. This does not only apply to the filmmaker.

Excerpts of Matthias Fritsch systematically set up archive can still be looked at – of course under consideration of the verdict of 2014. All together it includes thousands of images, videos, emails, blogs, articles, essays, legal documents and fan objects.

We can still not fully comprehend how such an internet meme develops. Which exact conditions have to apply, to create such extensive popularity? It seems to follow a somewhat unpredictable, chaotic principle. Besides the fascination for this phenomenon, further questions arise: How can we deal with the problems this case provides for the future? What about the right to be forgotten? The freedom of art? Which impact does the risk of being filmed in public have on our awareness and our behavior? What about the omnipresent possibility that our picture is separated from our personality and at the same time is still connected to it? And how do we deal with this without taking away society’s possibility to develop culturally?

Berlin 2007-2015 / 10 Monitore, 10 HD-Player, Kopfhörer, Plots, T-Shirts, Bücher, Skulptur

Der Wanderer – Manuel Frolik (Kulturbahnhof)

This hiking tour seems to have no end and yet the hiker presents himself with a steady flow of power in his forward thrust, which leads him through this forest, through green meadows, along river courses or through swamps with dead branches and over rough rocks. He remains to pursue his path with determination. Neither effort nor hardship can be sensed, nor an optimistic mood or fatigue. This is why we – while following him cinematically – cannot predict how long he has been en route, let alone how long he will be able or willing to continue this way. After some time, one notices that the landscapes begin to repeat themselves and one begins to suspect that the hiker is moving in circles. And indeed, this work is an experiment with the video loop as a cinematic structure. What seems like a repetition is a sequence of singular films, which have been shot at the same location but are cut together from different sources of film material. The consequence of scenes and therefore the landscapes of the seven five-minute films are the same, the shots and details vary. The question arises, how long we would we watch a film before noticing that the replay actually is not a replay and what it means when – after seven films – the actual repetition starts;when the film is really looped in its presentation as an installation.

The hiker himself and his presence seem to fall a bit out of time. A vest and a striped shirt, a backpack and a wandering stick are far from today’s functional wear and so he seems much more like a contemporary of Caspar David Friedrich than of our days. Therein lies a desired image, which has existed for a long time in our culture. The longing for a simple life in harmony with nature already existed in antiquity in the imagination of a rural Arcadia. Other examples are the idea of the great hike in Johann Gottfried Seume’s book “Spaziergang nach Syrakus” (“Walk to Syracuse”, 1803) or the imagination of a retreat to the woodlands in Henry David Thoreau's cult book “Walden” (1854). All of these images are also images of masculinity; blue prints, which today are interchangeable and available as one identity among many. In his work Manuel Frolik stages such spaces and images, myths of male freedom and self-determination; for example as a sailor, as a mechanic or as the cool friend of Dash Snow or Kurt Cobain. But this does not happen without ironic distance: his sailor is a corpse, and Dash Snow as well as Kurt Cobain are also already dead, therefore “cool” per se.

The hiker undertakes his hike as a projection in a forest worker’s hut. The image appears as a kind of slide picturing longings, like a photo-wallpaper presses the dream of a far away world onto the domestic walls. Frolik adds objects to this room, which make it seem like a life-size doll house or like rooms of the past frozen into big dioramas, which one can come across in local history museums.

Dresden 2014 / Video-Projektor, HD-Player, Verstärker, 2 Lautsprecher, Subwoofer, Objekt (37 Min.)

Apartment Building – Florian Göthner (Kulturbahnhof)

An apartment building offers room for people to create a home and a place of retreat. Divided into several apartments, which are filled with useful and decorative things, its interior is an expression of individuality, well-being, life-concepts and the realities of life. Thousands of these buildings, which are hardly distinguishable from another in their modern architecture, shape today’s cityscapes; only every so often is there an historic building complex. They share the same function, even though their variety of forms lays hidden from us with their privacy and intimacy.

The APARTMENT BUILDING, into which Florian Göthner leads the viewer, almost has a threatening effect looked at from the outside but – in its schematic style – can be regarded as representative for its type. Since the building has never been entered, we also cannot leave it. This first paradox sets the mood for a spooky walking tour through a complex spatial order, which is especially characterized through light and the absence thereof. There seems to be no visible difference between artificial and natural light. Therefore the interior and exterior do not seem to be separated. Carefully one’s view glides along dark hallways and stairs and time and again advances into rooms, which show no signs of human life. Solely light and space describe movement, shape and action. Hence they function as scenery and performers at the same time. In the uniformity of the architecture the viewer is subject to increasing disorientation, which is again subject to a strange kind of rhythm: some rooms reoccur, but occur differently each time; the view partly goes into detail but stays distant at the same time. And even when there are moments, in which the movement stops in its spatial thrust, it continues atmospherically through the perpetual and recurring music, which builds up, gains momentum and then falls apart – only to be built up from anew. So we keep expecting – feeling pressed by the eerie uniformity – that behind the next corner something will be revealed; we almost hope it does. But we remain caught in uncertainty as well as in the building itself.

Only a night guard, unreachable through his spatial separation, watches over the events and fulfils his patrol persistently. Just arrived in his office, he harkens and continues his ways but without ever tracking down anything. The night guard, however, presents the crucial hint to the viewer, revealing how Florian Göthner’s collages are laid out. His figure derived from the crime thriller “Le Cercle Rouge” by Jean-Pierre Melville, who offers an interpretation of the complex room structure of the APARTMENT BUILDING through the artificiality of his film sets. For the room images and arrangement are quotes from cinematic and literary sources of different genres and epochs; they pick up their atmosphere and hint to possible scenes, which never arrive. They prove the artist’s interest in the fragmented clues of architecture, which films and literature provide from time to time.

Leipzig 2015 / Monitor, HD-Player, Kontrollmonitor, DVD-Player, Collage (15 Min.)

Talking Business – Kerstin Honeit (Kulturbahnhof)

TALKING BUSINESS refers to the tense initial meeting of Alexis Carrington Colby (Joan Collins) and Krystle Carrington (Linda Evans) in the first episode of the second season of the Reagan-era TV series “Dynasty”. But Honeit spares us the spectacle of the famous cat fights that marked the women's relationship and secured the show's ratings. Instead, she cleverly subjects the scene of the women's initial meeting to a series of displacements, from one screen to the other, from English to German, and – most strikingly – from on-screen pretense to off-screen investment.

The off-screen of Honeit's “Dynasty” is specified first and foremost by Gisela Fritsch and Ursula Heyer, the actresses, who lent their voices to the characters of Alexis and Krystle for the German synchronized version of the show. Working closely with the two voice actresses in their seventies – Gisela Fritsch sadly died during the course of their collaboration – Honeit teases out the tensions between speaking a part and playing it, between dubbing glamorous women and embodying them. At one point over the course of rehearsals with Honeit, Heyer reflects on the empowering act of employing Alexis' turns of phrase in her daily life: "I thought if I use my own words, I won't manage to engage people. But when I said a sentence like, 'It'll snow in hell before I see you again,' then people laughed."

In the studio setting, she even dubs herself from earlier rehearsal footage with the actresses. Throughout the piece, however, she functions more like a moderator, who enables Heyer and Fritsch to give voice not merely to the words written for famous TV stars, but to those describing their own conflicted relationship to female embodiment and mediated presence.

What Honeit is after is a critical detecting of "the technologies of gender". That becomes clear when we hear an audio recording of Heyer's resonant voice as the affected Alexis, and at the same time watch archival footage of the actress' transformation into Joan Collins at the hands of a hair and makeup artist. Next to it we see an image of a spinning reel-to-reel audio player atop Heyer's newspaper clippings about her life as Carrington/Collins. Honeit's synchronization of sound and images across these screens brings into focus the mediated and discursive production of a split female subjectivity, one produced at the intersection of representation and self-representation, at the crossroads of social technologies, institutional and critical discourses, and media practices.

Berlin 2014 / 3 Video-Projektoren, 3 HD-Player, Verstärker, 2 Lautsprecher, 3 Leinwände (13 Min.)

Two Skies – Lukas Marxt (Kulturbahnhof)

From the platform of an oil rig we dive into the setting of two firmaments, whose physical force we cannot escape. What affects us through both surfaces, is their respective depth. This is where the work releases a multitude of associations and continues them. Already in its title, TWO SKIES describes the oscillation of the work between conflicting principles and intellectual spaces of possibilities: Stagnation and movement, surface and depth, sky and firmament, utopia and dystopia…

Lukas Marxt takes us to the gas and oil fields of the Tampen area, far up in northern Europe, in the Norwegian Sea. From there he shares with us the views upon the sea at two different times of the day, sunset and sundown. Sharing is the principle of the installation TWO SKIES. He assembles the images in an overlapping and point-symmetrical way and therefore irritates the viewer with the optical illusion of a hall of mirrors. Is it all not to be taken seriously? Is the montage merely for the effect of a mirroring trick? The effect of the images suggests something else. We find ourselves in a calm but at the same time pressing and heavily pushing sea. In order to survive in such a surrounding, we have to know the exact position and this becomes the first big challenge for the viewer: Because hardly any of our visual experiences corresponds with the image world of TWO SKIES. Lukas Marxt leaves us without a possibility to believe that we are standing solidly at the coast and are watching the sea from a safe distance;the impact of the water is too immediate, direct and concentrated. On the other hand, he shows us through the calm positioning of the camera that we cannot be standing on a boat, which lowers and raises itself, maybe on the way out towards the horizon, utopia or homewards to a safe haven. And into this uncertainty of one’s own standpoint images inevitably immerse, which have been of great significance for some time now, telling of fates, of dreams, fears and unfortunately also of death. The sea below us, the sea above us. And suddenly the trick is gone and everything turns serious.

But Lukas Marxt is more exact. He questions the places of his visual world with subtle means: in lengthy shots and with quiet sounds. And exactly there in the soundtrack of the installation, where the initial original sound of the sea steadily develops into a compressed noise, a level elevates, which becomes very concrete. The noise is identifiable as white noise, which is used in the engineering sciences to illustrate disturbance in an ideal model. Which model we are dealing with in this case becomes clear, when Lukas Marxt audibly reflects the place of origin of his work. He uses this method to show the structures lying underneath the surface of the water or – if one considers the title of the work – lying in the heights and applies an almost mythological severity to the obvious mistakes, according to the image. For when the white noise ultimately breaks away into a sound reminiscent of the singing of the sirens and the horizontal line dissolves into white light, the question remains if TWO SKIES is a mirror image of an apocalyptical prevision or a hope for utopia in the near future.

Snorre A, Köln 2015 / 3 Video-Projektoren, 3 HD-Player, Verstärker, 2 Lautsprecher (4:24 Min.)

Skulptur21 – Gerald Schauder (Kulturbahnhof)

The primary difference between film and sculpture is their difference in temporality. Films develop in a linear fashion, as a chronological sequence. Sculptures are given as a whole. The viewing of it can begin at any point and from there can skip to any other point. The design and structure of a sculpture can attract interest by generating emphasis, which can draw attention through levels of brightness or special contrasts of form.

In film, this kind of emphasis becomes effective only as part of a dramaturgy. A rigid cut, the sudden change from light to dark colors, sensitize the viewer for the moment, which is set so permanently in the viewer’s memory. These differences between different kinds of media have been part of art-theoretical reflections since Lessing’s “Laokoon” (1766). This makes it possible to further evaluate the specifics of art works.

Gerald Schauder confronts us with the combination of a film and a sculpture, which directly refer to each other. The sculpture appears as a three dimensional model of what can be seen in the film as a two dimensional image. The system corresponds more or less with the system of a computer tomography. In this method several layers of a body are aligned and then put together to a virtual three dimensional model.

One film whose images are conceived as a constant sequence of cuts by the artist, is Hans Richter’s “Rhythmus 21” from 1921 or, depending on the dating, 1924. This work, considered an icon in the genre of abstract film, consists of swelling and subsiding of geometrical forms, of squares and rectangles. This sometimes happens fast or slowly. Every now and then there are jumps and several forms act, pulsate and interact with one another. Schauder transfers these movements into a spatial model by applying three minutes of film into the eight meters of length of the sculpture.

The format of the film, which possibly could vary depending on the area of projection, is determined to a cross section of 21 x 27,2 cm of the sculpture. The colors of the surfaces in Richter’s film, black and white as well as shades of gray, are also found in the sculpture. The sculpture seems like the most accurate translation of the film as possible, with the essential difference of successive sequence of film and simultaneity of the body in the sculpture.

Schauder's transformation and reference of the historical work of 1921 can be set in context with the historical discourse around the self-image of the present in the tradition of modernity. The interest for the rationalization of forms, which determined the design and architecture of the 1920's in a particular way – “Bauhaus” and “Neues Bauen” – finds its continuation in the designing of our day-to-day world;even today with extensive consequences. They can be sensed, among other things, in the relation between the real spatial accessible body and its digital simulation;for example in the case of built architecture, which offers a traceable draft from the computer. So perhaps Richter’s “Rhythmus 21” has to be interpreted in the sense of a temporal inversion – and with an appropriate amount of irony – as a translation of Schauder’s SKULPTUR21.

Köln 2015 / Video-Projektor, DVD-Player, Objekt (3:23 Min.)

Paradies – Max Philipp Schmid (Kulturbahnhof)

In a greenhouse dipped in darkness, a cold ray of light falls onto a middle-aged man in a shirt and tie, who – in silent solitude with the decorative plantings – is staging a chamber play. Sitting at a table, a collection of index cards lying in front of him, which he picks up and mixes again and again, reading out aloud words he finds on them into a microphone. Occasionally he remains silent in a meditative way and creates soundscapes of tropical animals, which he produces with his voice and other analog tools. Even though we are witness to their creation, they seem absolutely credible, since they form a perfect symbiosis with the artificially planted botanical world of the greenhouse. “After the artificial flowers, which imitated real flowers, he wanted natural flowers, which modelled themselves on fake flowers.”[1] With the protagonist’s proceeding uncertainty and perplexity, the plants transform into unreal dancing objects, which to some extent appear like insects. He reaffirms himself and repeats: “And it was good, all good”, because his dream of paradise “far from hardship and free of misery” will probably remain unfulfilled.

In his work PARADIES, Max Philipp Schmid broaches the issues of our desires and our ideas of secular paradise and its manifestations in everyday life. For this he weaves together quotes of Hesiod, Paul Gaugin, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Joseph von Eichendorff and Lucius Burckhardt, among others, into a multi-faceted complex of ideas, which he lets the protagonist create. If in the first part of the work he is still trapped in the darkness of the greenhouse, which may represent our fascination for exotic plants, as a symbol of the search for paradise in foreign lands, far away from the “tyranny of the hectic-mundane”, the artist gives us a hint about the nature of our desires in the second part: “Peirideisa: Paradise: Enclosure”. The word derives from the Persian and describes the enclosed, the area closed off from the outside. Is our longing for paradise a search for something, which only belongs to oneself? Something, which is dreamed and created from one’s own imagination, a place of identification?

“Paradise is a garden-like existence of the world.” On three screens, which are presented in a second room, we see pictures of enclosed, properly trimmed private gardens, balconies with plants and windows entwined with ivy. Again and again, the tree of life reappears as a limit, which can be seen as the ideal of suburban life. In the design of suburban landscapes, the gardeners manifest their moral values and ideals of social life. But the images also show, that the longing for paradise, in the form of the forever same uniformity of gardens, cannot fulfil our quest for individuality, and so we search for substitutes far beyond the familiar. In the end, also the palm trees and cacti, which are occasionally planted in shopping centers and concrete landscapes, cannot satisfy our longing. And so it continues “further from object to object, from substitute to substitute, because it is never fulfilled”.

Basel 2015 / Video-Projektor, 3 Monitore, 4 HD-Player, Verstärker, 2 Lautsprecher, Subwoofer, 3 Kopfhörer, 3 Stühle (8 Min.)

Untitled – Daniel Stubenvoll (Kulturbahnhof)

What all don’t we carry through the city? We are constantly busy carrying something back and forth: from little to big things. Light things we are able to carry ourselves but for the big and heavy things we need adequate equipment. People are also transported throughout the city, though usually in vehicles. Only seldom do we see people being carried by other people, at least not grown ups. Daniel Stubenvoll lets people carry people through the town, mind you: full-grown adults and no children. The carried people act in such a strange stiff and still manner, almost as if they were life-size dolls. Only the indication of a certain mobility lets us recognize that we are dealing with live transported goods. The question arises whether the carried people are taken voluntarily? Could it be that in the end they are being kidnapped? What speaks against this scenario is that they don’t show any sign of struggle. But aren’t we also sometimes involuntarily kidnapped without even noticing? Films carry us off into different worlds or different times, even to the stars, and commercials lead us to the supermarket shelf. But what if we enjoy being carried to these places and the people carrying us are the real enslaved fulfilling compulsory labour?

The place where these peculiar events take place is not just any town but Bejing, the capital of an enormous empire with more than 20 million inhabitants. One can easily imagine the bustle that goes on in such a city and also the vast amounts of people and material goods being transported, making it necessary that the city functions well. The necessary activity corresponds well to our imagination of the remarkably successful economic realm of China. Maybe this is the reason why nobody but ourselves standing in front of the video seems to question what is going on? What we see makes so much sense due to the continuity of the film. The things that have do be done are done and everybody knows it. Even this is an aspect of economic success: Everyone agrees and works towards success without question.

This success is clearly visible in the background of Daniel Stubenvoll’s images: sky-scraping buildings of the 21st century. Perhaps religion previously fulfilled the need for us to direct our view upwards. But today the temple buildings seem a little inferior next to modern skyscrapers.

Stubenvoll films his carriers and the carried with a Japanese camera using an Italian tripod. He refers to this specifically in the title of this work and therefore emphasizes the technical conditions. Also here somebody is obviously carrying someone else and by doing so creating pictures of mobility, filmed from a static position.

Filmed with Fujifilm X-E1 16.3MP Compact System Digital Camera with 18-55mm Lens, SanDisk Extreme Pro SDXC 64GB Class 10 SD Card. Mounted on Manfrotto 496RC2 Ball Head with Manfrotto MKBFRA4-BH BeFree Tripod

Peking, Darmstadt 2015 / Monitor, HD-Player (10:07 Min.)

Experimental Archeology: The Space Beyond all Illusions – Mathilde ter Heijne (Kulturbahnhof)

EXPERIMENTAL ARCHEOLOGY: THE SPACE BEYOND ALL ILLUSIONS shows video material shot at the four day ritual firing of clay sculptures in the Black Forest during a full-moon cycle in the Summer of 2014. A crew of experienced fire masters conducted the firing of the clay sculptures, by placing them into pit hole fires and other low firing ovens. Corresponding with the creation of large iconic clay sculptures, participants were invited to take part in shaman-led Ayahuasca ceremonies. In the videos, one sees the collaborative set-up of the full moon performance and how participants are guided through the ceremonies, which accompany the firing of the sculptural reconstructions of archeological artifacts dating from 23.000 to 30.000 BCE. Significant for the artist because the artifacts existed in a time before patriarchy;the invocations question how power structures from former times can affect present-day structures, which again are dictated by a long-standing history of patriarchy. Through the ceremonies, the participants set up the parameters for a utopian state of togetherness, recalling the time around 24.000 BC, which is clouded by many mysteries, as few documents from that time period remain. Thus, fictional retellings blend together with the fabric of history, so that the sculptures can be seen against new contexts that are neither historical nor contemporary.

Part fiction, part documentary, THE SPACE BEYOND ALL ILLUSIONS confuses the parameters of reality and structures of belief. The recordings for the video installation were not documentary records of the actions taking place, but meant to reflect the subjective views of the camera people and reveal the digital and analogue materiality of the apparatus. Both of these conceptual alternatives to documentary production were crucial in hinting at another reality beyond visual sight: A Kinect Xbox camera captured 3D data, a remote controlled infrared camera captured images at random, and kaleidoscopic lenses disguised the view of an old VHS camera.

The VHS video capturing device evokes the analogue, which prefigures the digital. This is perhaps an aesthetic illusionary motif hearkening back to times which valued the collective as a source of power and a tool for solidarity. The ritual worship – in this case – is less about bringing a divine or spiritual body into the world, but rather about constructing the necessary circumstances for such a visitation to take place: a visitation that could overshadow rather than foreshadow a future patriarchal binary. For these reasons, the camera obscures the vision onto the performance in order to force the viewer into a similar open position, so that he/she can feel the presence of the analogue goddess through sensation. The public is invited to lie down inside the geodesic dome made from wooden triangles, where all of these captured images cascade upon the viewer.

Vanessa Gravenor

Berlin 2014 / 5 Video-Projektoren, 5 HD-Player, Verstärker, 2 Lautsprecher, Objekt (25 Min.)

The Tallest – Rebecca Ann Tess (Kulturbahnhof)

Rebecca Ann Tess’ video work THE TALLEST already conveys the central paradox in its title: towers rivalling to be the world’s tallest. The superlative is the grammatical form, which cannot be increased, is the vanishing point of the super, mega, hyper tall towers, THE TALLEST presents, but they are only temporarily the tallest, the highest – this can always still be increased. The dimensions that come into play in this competition – as measured by conventional ideas of what a building is – long ago became absurd, unreal.

For this, Tess has found a convincing form for the unrealness of supertall towers. Although it is based on detailed research and footage recorded onsite (exceptions: the Mecca Royal Clock Tower, which Tess could not visit, and the Kingdom Tower, which has only just begun construction), she has abstained from showing the towers’ surroundings. Highresolution photographs provide the basis for an animation of each tower, in which they appear ethereal. The towers move across the screen, the artificial gaze gliding slowly up them. One seldom sees the base or tip of the towers. In the case of the Burj Khalifa, the animated shot begins in the lower third and, after almost two minutes, it still hasn’t reached the top. For the entire show, panoramic long shots are resolutely denied. The images also abstract from any movement; neither humans nor other mobile elements are shown. Even the skies are cloudless, monochrome greyish blue to white. Movement comes from the image alone: the only thing that appears mobile is that, which is static, the tower.The visual abstraction and the reversal of movement infiltrate the impression of reality, the phenomenal realism of the cinematic images. Instead it is the aesthetic aspects that are highlighted, shimmering between the poles of sculptural and ornamental. Sometimes the beauty of volume is emphasised; sometimes the image is tipped over flat. The elegance has a cooling but not sterilising affect. Despite all of the formal austerity, Tess also takes liberties in variation and modulation: tipping the towers over into the horizontal, slanting to the diagonal, adapting the scanning speed to match the form of the tower, alternately accelerating and slowing down. Both aspects are matched by the soundtrack. The voice audibly originates from a computer and is as inhuman as the buildings, imitating their technoid character. (One perhaps thinks of old science fiction films, the spaceships from “Star Wars”.) The text varies between information, which could in part originate from advertising brochures and with personal impressions. Every tower is introduced with a catchy refrain that gets stuck in your head: “tall, super-tall, taller than tall”. The voice ensures the documentary character of the work and in doing so, it also recalls the indexical dimensions of the recording as well as reflections on the geopolitical shifts.

The specific tension of Tess’s work can therefore be described as a double balancing act between documentary and abstraction; between ironic-critical distance and affirmative-aesthetic contemplation. In the era of turbo-capitalistic superlatives the aestheticized, the absurd, and the abstract do not form an opposite pole to reality and its authentic reconstruction, rather they become their integral characteristics.

Berlin 2014 / Monitor, HD-Player, 2 Kopfhörer, 2 Pipes, 2 Barhocker (14 Min.)

Center of Doubt – Ivar Veermäe (Kulturbahnhof)

With its nine video channels, Ivar Veermäe’s installation creates a cool and technical atmosphere. Images, which seem to be of taken by military satellites from radar stations are next to impressively monstrous pictures of data centers, which appear threatening at first sight and direct the attention instantly to what lies behind the smartly designed interface of communication technology and cloud computing. Closer inspection shows that CENTER OF DOUBT is the result of an extensive artistic research project with the aim of studying different approaches of visualizing digital infrastructures. Which images are used by IT firms and which images would be considered to portray abstract communication technology from an artistic view? Thus, it is a matter of making the things visible, which, for instance, remain invisible in the daily use of the internet – industrial plants with server cabinets, which use energy and need to be protected and cooled. In this long time project, Ivar Veermäe set a time frame, which ranges from the beginnings of visual interfaces to the net infrastructure of today. It cannot be considered a finalized research project, just the opposite: It will be continued. Which raises interesting questions, for example: Which data centers will grow in the next years? Where will we see stagnation and where will new ones be built?

Currently Veermäe subdivides his project into six areas, of which three parts "The Formation of Clouds", "We are as gods and might as well get good at it" and "Patent Application Data" deal with the same topic from different angles: firstly, with satellite images of data centers, secondly, with pictures from the Internationale Funkausstellung Berlin (International trade exhibition for electronic technology in Berlin) and thirdly, with diagrams presenting patented structures for the operation of data centers. The other three parts "Echelon", "High-Tech Fort Knox" and "Crystal Computing" deal with the historic places of the communication interception stations Teufelsberg, Brocken and today’s Bad Aibling as well as the specific European data centers of Google and Telekom. As can be expected, Veermäe’s requests for filming permits in the inside of the data centers were denied by the respective companies. But his recordings of the outside of the centers, with their steaming cooling units, make up a highlight of his installation. These impressive images of one of the largest Google data centers illustrates clearly in which dimensions the internet continues to grow and how with it the political and ecological problems become increasingly significant.

In the accompanying text, Veermäe cites, among others, Steward Brand as a pioneer of the internet, which he sees as a tool for personal liberation and whose vision is more and more under pressure due to some few monopolists. This is merely one of many cultural and economic researches, which Ivar Veermäe explores in his project and in the end lays the grounds for a critical position by choosing the title CENTER OF DOUBT.

// In the course of the interdisciplinary conference and workshop summit interfiction Paolo Cirio and Ivar Veermäe will talk about their works.

Berlin, St. Ghislain, Biere 2012-2015 / 3 Video-Projektoren, 6 Monitore, 9 HD-Player, Verstärker, 2 Lautsprecher

Halit-Straße, Kassel, Hessen, Deutschland – Fritz Laszlo Weber (Kulturbahnhof)

On April 6, 2006, Halit Yozgat was murdered by the so-called “National Socialist Underground” (NSU). Halit Yozgat was the owner of an internet café on the Holländische Straße in the northern part of Kassel – a quarter that is characterized by migration, students’ life and traces of industrialization. Halit Yozgat became the ninth victim of the NSU. Unnoticed by the public, the rightist terrorist group, whose circle of supporters included members of rightist associations and even informants for the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, murdered eleven people. Their victims were mostly business people and entrepreneurs, which became – as representatives of a despised culture – the target of the perpetrators.

After the belated solving of the crimes, Halit Yozgat’s family demanded a clear gesture of commemoration: The renaming of Holländische Straße, the place of the crime as well as the center of his daily life, into Halit-Straße. This demand was harshly denied by the local media as well as local politicians. As a necessary political compromise, a small square in Kassel’s northern part was renamed. In HALIT-STRASSE, KASSEL, HESSEN, DEUTSCHLAND the demand to rename the street is connected to globally accessible and circulating photos, map illustrations and satellite images: It becomes clear how tangible and symbolic a radical act of renaming a space can become. (This is why this form of commemoration is used for people of public and military life, who are considered important.)

The demand of Halit Yozgat’s relatives to rename the street clearly shows the actual problem: the lacking visibility of the victims. This disproportion is also reflected in the media coverage, which mirrors numerous portraits of the perpetrators with the lack of interest in the victims. While the backgrounds, names and personality profiles of the perpetrators receive constant media attention, the victims, their families, their names and story often remain unheard and unseen. Countless images of the NSU perpetrators are published, while the murdered were portrayed on the same lined up passport photographs, similar to photos used for a wanted list, visually as well as symbolically freed of any individuality.

The video work is the result of research conducted by the artist, who reveals his ways of research, moving from news sites with great public attention to resistant media archives. Instead of producing new images, Fritz Laszlo Weber analyzes and links those images and bits of news, which circulate through the net and create narratives. At the same time, thoughts on visibility and structures of power are expressed as subtitles, which appear under browser windows presenting images and documents. Matter-of-factly HALIT-STRASSE, KASSEL, HESSEN, DEUTSCHLAND shows the strategies and politics of “Showing”, which decide on a daily basis which news, which stories, which names, which backgrounds and which people are seen and which are excluded from public awareness.

Kassel 2014 / Monitor, 2 Tablets, Verstärker, 2 Lautsprecher, 3 Plexiglaswände, Sitzelemente (16:18 Min.)